“internet down :(“by kirk lau is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Danielle Tessaro, Jean-Paul Restoule (@JPRestoule), Joseph Flessa, Carlana Lindeman (from the Martin Family Initiative), and Coleen Scully-Stewart wrote The Five R’s for Indigenizing Online Learning: A Case Study of the First Nations Schools’ Principals Course.

The title of this journal article instantly grabbed me. In my context, working in a Northern Canada setting with a high percentage of indigenous youth, I am always interested in ways to enhance the educational experience of our youth.

My first reaction, as I was reading the abstract and finding that the “article focuses on the creation, implementation, experiences, and research surrounding the first online professional development course for principals of First Nations schools across Canada,” (Tessaro et. al., 2018, p. 125) was asking if this even makes sense.

In my limited understanding and experience, veneered with a settler lens, culturally relevant Indigenous education starts with the land and people that you are specifically working in/with. From there you consult with the Indigenous community and get guidance about what is appropriate and desired for you to teach. You then look at your curriculum and find any places that the two overlap, and then you teach it.

The other way to indigenize education, again through my settler lens and experience, is to realize that the youths are the culture, so bringing their voices and experiences into the lessons and providing them the lens and voice to steer the lessons and inquiry is allowing their culture to lead the lesson.

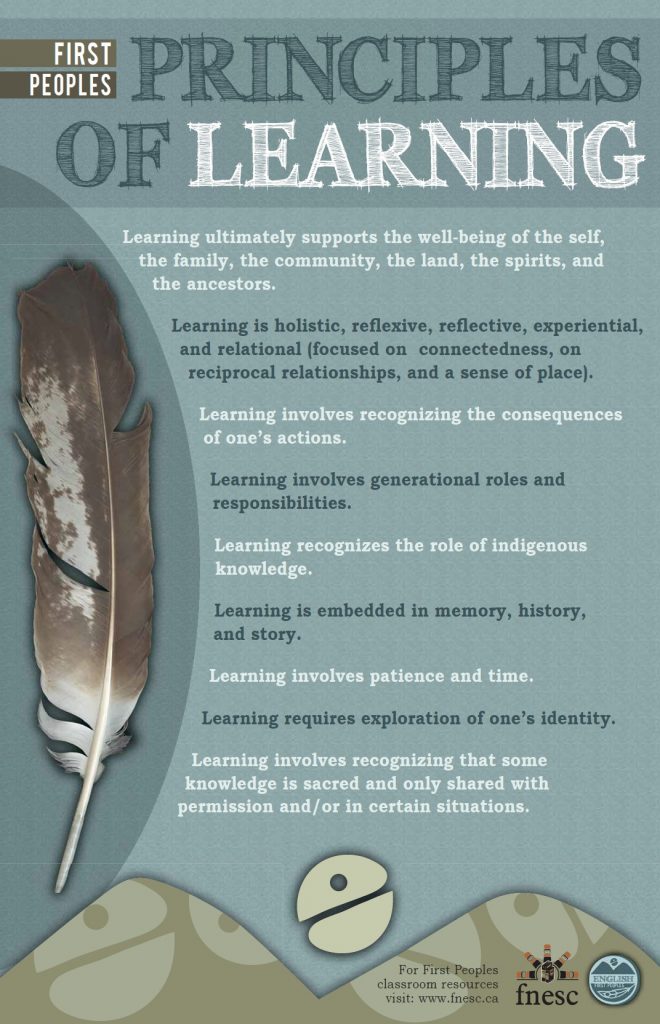

There is an informative website, that is recommended by the government of British Columbia, that can help inform you about the First Peoples Princples of Learning was created by Jo Chrona (@luudisk), who also has an interesting blog located at https://luudisk.com/. I recommend looking over the site to help inform you about the different aspects of indigenizing education. The website will guide you through the nine different First Nations Principals of Learning, as shown on the poster to the left.

The concept of creating an indigenized curriculum that would apply to principals across Canada, that would be online, seemed to me like a large stretch. I was curious, and at this point looked into the authors to find out their credentials. Feel free to have a look at their credentials that are linked to their names at the start of this post. Needless to say, they are credentialed. Finding out that they probably knew exactly what they were talking about hooked me.

Right at the start of the article Tessaro et al. started to identify some of the concerns I initially had. Here are some quotes, that are from the start of the paper, that demonstrate they had the same thoughts and concerns that I did:

- “A prime example of this conflict stems from Indigenous education usually being situated in a specific environment and community context” (stated by Restoule, 2017 in Tessaro et al., 2018, p. 126).

- “Online education tends to be low context so that it can be consumed by any user, anywhere, whereas traditional Indigenous education is highly contextual” (Hall, 1976 as cited in Tessaro et al., 2018, p. 126).

Not only did Tessaro et al. have the same concerns that I did, this brought even more interest to me that they may be on to something here.

On a side note, I feel the need to clear up one point. I have not read Hall’s paper, however I do believe online learning has significantly changed since 1976. Take the EDCI course that I am currently taking with Dr. Valerie Irvine (@_valeriei), for example. Half of the class is participating remotely, but through the use of synchronous videos, blogs (like this one), and back end chats on WhatsApp and Twitter, we are getting very connected to each other. I also know, through our Northern Distance Learning program in the Northwest Territories, that culturally relevant education is possible through an online system. Both of these examples react to students. I think that is a key aspect. Trying to create a general course that would serve everyone across the country is what I was having a challenge visualizing, not an online course that is culturally relevant.

As I continued to read the paper it became more and more evident that Tessaro et al. may be onto something very significant. They again stated the importance of local context in Indigenous education stating that “successful Indigenous education approaches, teacher and learner often have knowledge of each other’s backgrounds, capacities, and learning experiences, thus enabling teachers to tailor lessons accordingly” (Tessaro et al., 2018, p. 131). They also readdressed the challenges of working Indigenous education into the classroom stating that “in some ways, the virtual space of the online classroom can mean that the learning is rather place-less” (Tessaro et al., 2018, p 131).

Their approach for this classroom was to create 10 course modules. “Through its 10 modules, the course trajectory was designed to move from the exploration of principals’ relationship with self, to the school, to school community, and then to structures beyond the community” (Tessaro et al., 2018, p 131). “Every module was organized around a query concerning principals’ everyday experiences, and activities and resources were organized to support exploration of the query” (Tessaro et al., 2018, p 132). Through the lens they created a course that in its design allowed for individuals to connect to their community, their place, their self, and build relevancy. This is indigenizing education. By creating a course that allows individuals to customize their individual learning, within some constraints, you are allowing that individual to be in control.

This speaks to the importance of creating an inquiry environment within our school systems to support Indigenous education, specifically within my school district, Beaufort Delta Divisional Education Council, where over 90% of our students are Indigenous. I have always been a proponent of inquiry because it makes a lot of sense to me from a pedagogical perspective. A phase that I have always held on to is “a problem is only a Problem (as mathematicians use the term) if you don’t know how to go about solving it. A problem that holds no “surprises” in store, and that can be solved comfortable by routine or familiar procedure (no matter how difficult) is an exercise” (Schoenfeld, A., 1983, p. 41). I believe that good problems can be a gateway into an inquiry style of learning, and this allows our youths to develop competencies that will serve them better throughout their lives than any facts of knowledge we can cram into their memories. I received a book by Trevor MacKenziev (@trev_mackenzie) called Dive Into Inquiry which I am very excited to read as I feel I need help and guidance to build up my inquiry teaching method.

All that being said, it never occurred to me, until I read The Five R’s for Indigenizing Online Learning: A Case Study of the First Nations Schools’ Principals Course, the important link that inquiry and indigenizing education can play.

This was my big ah hah moment from reading this paper. The more we can design an inquiry basis into our classroom, while respecting the five R’s (Respect, Reciprocity, Relevance, Responsibility, and Relationships) the better it will be for our children…and with careful thought and consideration, you can design this model in an online environment that is applicable to the whole country. Fascinating and exciting stuff!

As an aside point, in the Northwest Territories we are currently working on Education Renewal. One of the key aspects of this is the Key Competencies of an NWT Capable Person. It is intersting that a lot of our key competencies align with the Frist Peoples Principles of Learning. Watch the video below if you are interested in what we are doing in the North.

NWT Key Competencies, January 2017 from NWT Education Renewal on Vimeo.

NWT Key Competencies, January 2017 from NWT Education Renewal on Vimeo.

2019-07-20 at 9:04 pm

Great post! Informative and thought-provoking.